Rayonier is supporting the Cowlitz Indian Tribe’s effort to increase salmon habitat complexity by adding engineered log structures to the Grays River and creating new habitat for spawning and rearing salmon and steelhead.

GRAYS RIVER, Washington—Pete Barber has surveyed miles of the Grays River and its tributaries countless times, but one day he found himself in the middle of a rescue operation.

While walking the margin of the river channel, the Cowlitz Indian Tribe’s Habitat Restoration Program Manager’s footprint disturbed a new deposit of fine sediment. Within the new accumulation of sand and pebbles, he discovered freshly hatched salmon eggs, previously swept out of their nest, called a redd.

These juvenile salmon were buried and unable to swim out of the accumulated sediment, an unfortunate and likely common occurrence in the Grays watershed, due to a lack of logs and logjams to slow flood waters each winter.

Pete immediately got to work, manually moving handfuls of the tiny fish from the isolated puddle back into the river.

The experience underscored why the Tribe is undertaking a major restoration effort: adding thousands of trees to the active river channels across the upper Grays watershed.

The major effort aims to increase the roughness of the channel with wood additions and reconnect floodplains to create vital habitat for salmon spawning and rearing.

Our three-part video series and on-the-ground storytelling—years in the making—follows the Grays River restoration project coming to life, as the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and Rayonier work together to restore natural habitat, bring balance back to the river, and support the return of culturally and ecologically important species.

- How the Grays River Restoration Project Began

- The Significance of the Grays River and its Salmon to the Cowlitz Tribe

- Why have Salmon Populations Declined in the Pacific Northwest?

- What’s Being Done to Restore Salmon Spawning and Rearing Habitat

- The Plan for Restoring the Grays River to its Former Condition

- Putting the Plan in Motion: Placing Thousands of Trees in the Grays River

- Celebrating Early Results and Looking to the Future

How the Grays River Restoration Project Began

For years, Rayonier and the Cowlitz Indian Tribe have worked together as stewards in Rayonier’s Grays River Forest. Together, we have sought to restore the instream habitat and improve the health of the surrounding forest and watershed.

Project areas in some portions of the river are already responding. The new log structures are retaining gravels necessary for spawning. Gravel bars and shallow areas known as riffles are once again providing the diversity of instream habitat, required to help recover this local salmon and steelhead population.

The long-standing relationship between the Cowlitz Indian Tribe and Rayonier laid the groundwork for a shared vision to take shape in the Grays River watershed, as both partners recognized the urgent need to restore the health and balance of the watershed.

Watch Part 1 of the video series to see the project come together as we work to restore the habitat in a way that benefits the landscape, the water, the salmon and the surrounding communities.

The Significance of the Grays River and its Salmon to the Cowlitz Tribe

Known as “The Salmon People,” the Cowlitz Indian Tribe has relied on salmon for generations, not only as a food source, but also as a key part of the Tribe’s culture and traditions. The Grays River once provided enough salmon—and specifically steelhead—for everyone, however in recent decades the productivity of the river has plummeted below historic levels.

Why have Salmon Populations Declined in the Pacific Northwest?

Logging practices have improved over the years, with increasing regulatory requirements for harvest layouts and stream buffers, and best management practices specific to access road construction to support timber harvest.

Similarly, the science supporting salmon and steelhead restoration has advanced over the years. Scientists believed in the 1970s and ’80s that logjams restricted fish passage. They were subsequently removed with heavy equipment—even dynamite.

For example, this 1983 Stream Obstruction Removal Guidelines document, created by a consortium of fish and wildlife groups, calls for the removal of “obstructions” and “unacceptable flow problems.”

The logic behind this approach was driven with an assumption that removing logs would help salmon travel more easily to their spawning grounds from the ocean, allowing rivers to flow powerfully, like a “highway to the sea” for salmon. Since salmon and steelhead are born and rear in headwater streams before migrating to the ocean, the goal was to clear their path.

But without the natural logjams, rapid-flowing waters caused:

- Gravel needed for spawning to wash away, leaving bare bedrock behind

- Salmon eggs to be swept downstream, unable to remain protected in place

- Young salmon to lose refuge from predators without calm, shallow areas with cover

This led to fewer fish surviving as juveniles, and the salmon population quickly declined.

How Removing Logs Impacted the Grays River

Rayonier purchased the Grays River property in 2008. Prior landowners from the 1900s had followed the regulations of that time, often harvesting timber down to the river’s edge and following scientific guidance to clear logs from the river.

The removal of large, old-growth trees from the river’s edge deprived the system of trees large enough to remain stable once they fell into the river, forming large logjams over time. Without these large trees in the river, wood floating down the channel during floods will simply keep going downstream, instead of being caught in a logjam and contributing to instream habitat.

Historic harvest practices, combined with removing logs up until the early 1980’s, eliminated critical salmon habitat that depended on those removed log structures in the river: the still, shallow, gravel-lined pools critical for salmon spawning and rearing that develop around the logs.

In the Grays River, the effects of removing logjams in years past proved devastating.

Not only was there less salmon for the people and animals that rely on it as a food source, but the river also flowed much faster than it ever had. Upland floodplains dried out, causing major issues with flooding in towns downstream. In times past, slower-moving waters had allowed floodplains to engage in the forest, creating a complex habitat and allowing waters to distribute in a location that didn’t impact the human population.

What’s Being Done to Restore Salmon Spawning and Rearing Habitat

Today, structures like logs are being added back into rivers to restore ideal salmon habitats.

Forestry companies like Rayonier have also invested millions into removing or replacing road crossings that impede fish passage and the natural flow of waterways.

And, most importantly, partnerships have formed to restore many miles of rivers with a goal of restoring historic salmon populations.

The Plan for Restoring the Grays River to its Former Condition

The Cowlitz Indian Tribe led the five-year effort to plan, design, and implement this project in collaboration with Rayonier, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and many partners and funders including the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office whose Salmon Recovery Funding Board (SRFB) grants and Washington Coast Restoration and Resiliency Initiative (WCRRI) grant made this restoration project possible.

The Tribe’s plan began with a science-based approach to recreate the river’s natural conditions using thousands of trees placed strategically in the water.

A Collaborative, Science-Based Restoration Effort

Rayonier’s Senior Harvest Manager Mark Smalley explains that a combination of comprehensive studies and consultants were utilized to develop the best possible plan, with research beginning as far back as 2019.

“They designed the structures and how to place them, considering the flow of the river, where the gravels come from, how we want to retain them, and what would make the most sense for the salmon. It’s been quite an involved process. The result is a packet of plans and designs built from a science-based approach.”

What We Expect from Mimicking Fallen Trees

“In the future, we hope to see increased salmon runs and salmon survival,” Mark says. “The idea of adding structure is to retain gravels and sediment, giving the fish a place to spawn. To do that, you have to imitate the natural processes of trees falling over in the river, and then sediment collecting behind those logs. We’re trying to mimic what nature would do over time.”

Putting the Plan in Motion: Placing Thousands of Trees in the Grays River

After all the planning and research, it was finally time to put the vision into action. The team began placing thousands of whole trees into the Grays River.

This phase of the project was a major milestone, and one the Cowlitz Indian Tribe had been anticipating for years. The process required close coordination, innovative techniques, and a commitment to honoring the river’s natural processes.

Watch Part 2 of the video series to see how the team accomplished this remarkable undertaking.

Using Rayonier Timber for Log Structures

Rayonier timber played an essential role in the project, serving as the main material for the logjams.

“Wood is a key component to any sort of river system because it adds complexity,” explains Lauren Bauernschmidt, a habitat biologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). “It helps us reengage the floodplain, it gives fish a place to hide, it aggregates material, so it will actually hold back rocks and sediment.”

Using Whole Trees with Roots Intact to Slow the River

With Rayonier collaborating by providing river access, Pete and his team utilized ground crews as well as a helicopter to place wood structures in the river. To prevent them from washing downstream, they employed a unique approach: using whole trees with the roots still attached.

They treated 3.1 miles of instream habitat with more than 8,000 loose trees and engineered logjams. Boulders connected by cables were placed atop many of the tree structures, further anchoring them against high water events.

“The sheer quantity of whole trees and root systems mesh together and anchor the trees, while providing permanent structure and channel roughness,” Pete explains. “Slowing the flow of the river and storing sediment in the floodplain also reduces flood impact to the local community located downstream.”

While more than 8,000 trees sounds substantial, WDFW’s Lauren notes: “Having this amount of wood placed in the system is really a kickstart for this system to recover on the scale that is really needed.”

Transporting the Trees to the River

Transporting trees of that size wasn’t easy, but fortunately, they didn’t need to travel far. When a nearby stand was ready for harvest, Rayonier gave the Tribe priority access. Using grant money, Pete and his team were able to purchase 40 acres of trees.

Sevier Logging took on the unusual challenge of felling the trees while keeping their roots attached. Owners Jeff and Justin Sevier felled the trees, shook the dirt from the roots and smoothed the ground to prevent erosion.

Creating Engineered Logjams

Crews conducted the work in September, taking advantage of the river’s slow, low flow that time of year. Despite appearing haphazard, logs were intentionally placed in pre-determined spots. This precise placement was crucial to slow river waters and establish places for gravel and pools to form.

Some of this was done by helicopter, with ground crews marking the locations for placement with brightly-colored survey tape, then moving clear while the helicopter placed the trees and boulders. Other elements were put into place with heavy ground equipment in locations where the river was more accessible.

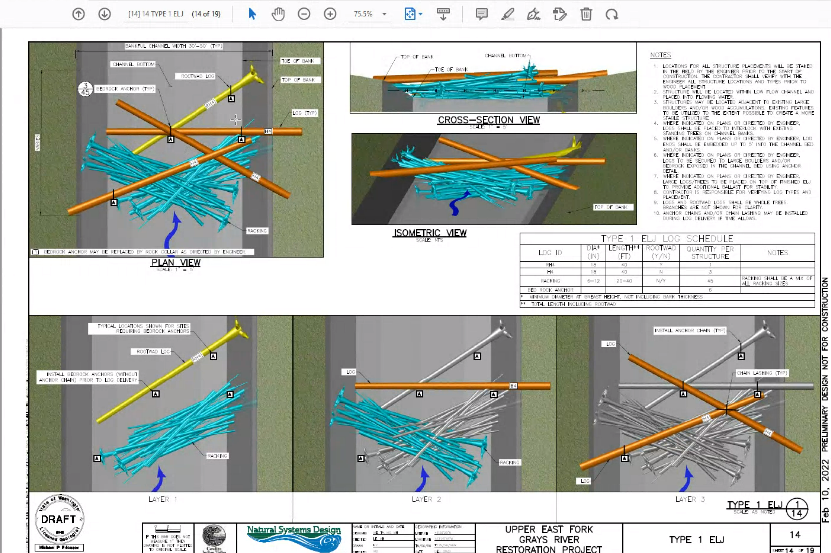

They followed blueprints to build engineered structures that provide layers of impact:

- The base layers utilize whole trees to slow water, capture gravel for spawning, form scour pools, and enhance channel complexity.

- Upper layers, composed of more trees and boulders, ballast the engineered logjams, anchoring the trees against downstream movement, and interact with higher flood flows.

Types of Engineered Log Structures

The team used a combination of different engineered logjam structures, each with a unique role in shaping the river:

- Type 1: Channel-spanning structures designed to collect large amounts of wood and sediment, raising the channel bed and significantly influencing the flow across the entire channel.

- Type 2: Bank-attached structures built along one side of the river. These help shape pools, bars, and flow patterns. Gravels typically collect in the slow water immediately downstream as flow is deflected to the opposite bank.

- Type 3: Smaller, bank-attached structures are used in the smaller treated tributary reaches and perform similar functions as the Type 2 structures, creating flow and habitat complexity, offering shelter and feeding areas for young salmon.

Celebrating Early Results and Looking to the Future

Months after the logjams were added to the river in fall 2023, the Grays River experienced record-breaking rains. The team behind the project was pleased to see that the complex structures stayed in place. The waters quickly delivered sediment into the system, and soon the bare bedrock began to disappear as it was buried with gravels.

Watch Part 3 of the video series to see the early results and hear what’s next for the Grays River.

Signs of Success in the Restoration Project

While the added structure is meant to continue to naturally develop over the years to come, there were encouraging signs of success already.

In the spring of 2024, Pete and Lauren found a steelhead “redd” — a spawning nest — in the treated area while they were walking the river. In the summer months that followed, the project site was filled with juvenile salmon and steelhead, hiding within the matrix of logs and logjams.

Pete said it was “proof positive” that the effort was making a difference and showing initial signs of recovery.

Continuing the Work Ahead

Over the years to come, it is expected the river system will continue to change, and the salmon populations with it.

The Tribe will continue to seek out additional opportunities along the river to further restore what was lost.

“These structures were tested, they survived and they’ve done what they were built for,” Pete says. “They trapped the sediment that was moving through, they’ve backed up flows, they’ve scoured pools, and all of the wood that we placed has stayed stable. It’s done what we had designed for, and that’s really something we’re quite pleased about.”

Leave a Comment