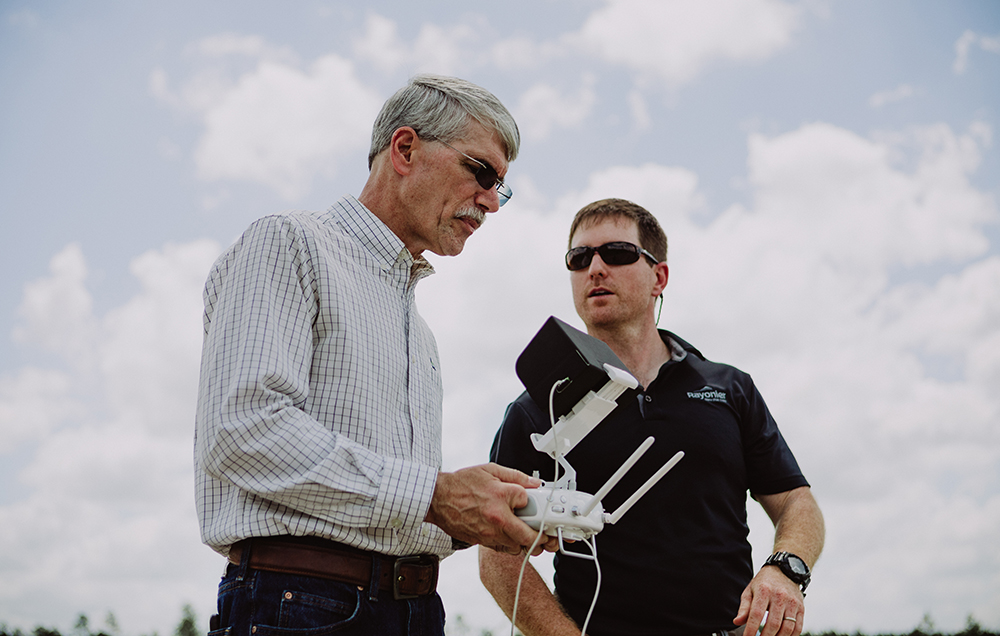

Drones have become an important part of Rayonier’s forestry operations. Our drone pilots share how they use this tool to gain a new perspective in the field.

For years, Resource Land Manager Neris Biciunas puzzled over how to get rid of an invasive plant that was harming trees on Rayonier’s Washington land. Called Scotch Broom, it is difficult to spot and nearly invisible from the air, except for a small window of time each year when it blooms with bright yellow flowers.

Then Neris, who’s based in Forks, Washington, became one of Rayonier’s drone pilots. He flew his drone as soon as the Scotch Broom plants bloomed, collecting aerial photos so he could develop a precise map of the plant locations across miles of forestland. Once the plants were located, his team was able to develop a treatment plan to get rid of them.

There are countless success stories like this that show how drone flights are impacting Rayonier for the better. They’re used to take a quick initial look at a stand of trees, to monitor a contractor’s work, to more safely assess the devastation during and after a forest fire, and even to create 3-D images.

After a preliminary “pilot” team tested how the company could use drones in 2017, Rayonier saw the potential and launched the program nationwide, encouraging at least one forester in every U.S. location to get their FAA drone pilot’s license. There are currently 30 pilots on our U.S. team.

In New Zealand, our first employee pilots were trained in early 2018 after a couple years of working with contractors to test the impact of drones. Now we have a drone in each of the five regions in which we operate, with 15 trained pilots. The New Zealand team typically refers to their drones as UAVs, which stands for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles.

“We have some clever, motivated people who are determined to leverage this technology—and technology in general—to do existing work better and, even more exciting, find new ways to do more than we could previously,” says Forest Information Manager Joanna Drabsch, who’s based out of Auckland, New Zealand.

A New Perspective

“A drone allows us to see something we wouldn’t have been able to see any other way. It’s a tool that gives us a whole new perspective,” says Technical Analyst Sara Bellchamber, a self-described gamer who organized the U.S. program.

Based in Wildlight, Florida, Sara says one way she uses her drone is to help Rayonier’s land resources team measure the depth of fill dirt pits using a program called Drone Deploy. The software uses images taken in a grid pattern and stitches them together into a 3-D image.

Sara says she has seen drones save costs, increase safety and save time throughout Rayonier’s ownership. In the South, for example, they minimize the gap in time between the harvest of a forest and the preparation of that forest for replanting during Florida’s hot summers.

“After a harvest, you’d normally have to fly a plane to estimate what it will take to prep the site [for replanting],” she explains. “In high summer, there’s a haze in the sky and planes can’t take clear photos through it. But drones can fly below the haze, getting us the imagery we need much sooner.”

While planes are still the preferred option for imagery collection, work doesn’t have to grind to a halt if a plane is not an option.

Working with Drones in the Forest

Blake McMichael and Dan Hildebrand, both Resource Land Managers based in Jesup, Georgia, use their drones when they’re in the field assessing forests.

“One of the best uses I’ve found is for site-specific management,” says Blake. “It helps me delineate where treatments are needed and where they’re not. It’s not replacing boots on the ground, it’s giving us a birds-eye view we’ve never had before.”

Eliminating Hours of Work

For Dan, who’s been a Rayonier forester for more than 30 years, his drone eliminates hours of work tromping through the forest to locate pre-commercial thinning candidates, trees with flaws such as forking that should be removed to make room for the optimal trees to grow.

When he first became a forester, “it used to be all boots on the ground,” Dan says. “But I’ve always been open to new possibilities.”

In hazardous conditions such as difficult terrain, drones can make a task much safer. Neris, the forester in Forks, used his drone to save himself from a long, cold walk to determine whether snowy roads would be drivable or not after a heavy snowstorm (they weren’t).

“It took me 10 minutes to do with a drone what would have taken me 2 hours to do on foot,” Neris says.

That sentiment is echoed by many drone pilots across many tasks: work can be done quickly, accurately and more safely by incorporating a drone.

“My favorite way to use the drone is by using the Maps Made Easy software to quickly map a large area in high definition, then be able to convert that to a file which can directly be transferred to our GIS system,” says Graduate Forester Patrick Dravitzki, who’s based in Whangarei, New Zealand. “This is great for doing harvest reconciliation mark ups as we get an accurate measurement of the area which has been harvested, then compare that with the volume recovered to get a volume recovered per-hectare.

“This also solved a problem, as previously we had to walk the perimeter with a GPS or hand draw on a map. This method is a lot safer, faster and accurate.”

Using Drones to Prepare for the Future

The drone pilots share files and tips with each other and come together for a regular cross-country phone call, hearing new ways fellow foresters have discovered to use their drones in the field and helping each other expand their skills. The team is continuously trying to prepare for what’s next: several of the pilots are even part of a Rayonier “super users group” tasked with staying on top of any future technological advances that could benefit the company.

Neris gives Rayonier leadership credit for supporting the program from the start.

“They were receptive, asked hard questions, listened thoughtfully, and let us check it out,” he says.

The result is a program that not only benefits Rayonier now (one forester said the information gleaned in a single flight saved more money than the cost of his drone), but it’s also positioning Rayonier for the future.

“Having a team of drone pilots, the infrastructure for the program, the experience and understanding how to use the data we’re collecting puts us in a very strong position for when the next development rolls along,” Neris says. “We’ll be ready.”

Leave a Comment