Working forests play a critical role in the quantity and quality of America’s water supply. We look at how the forestry industry not only protects water, but takes a proactive role in improving water supply.

BROOKER, Florida—Once upon a time, there was a massive body of water that flowed deep under the ground where it couldn’t be seen. It was so big, it stretched to four different states, providing drinking water for millions of people.

The story of the 100,000-square-mile Floridan Aquifer is so good, it almost reads like a fairytale. Found underneath all of Florida and parts of Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina, it provides billions of gallons of drinking water every day. It is one of the most productive aquifers in the world.

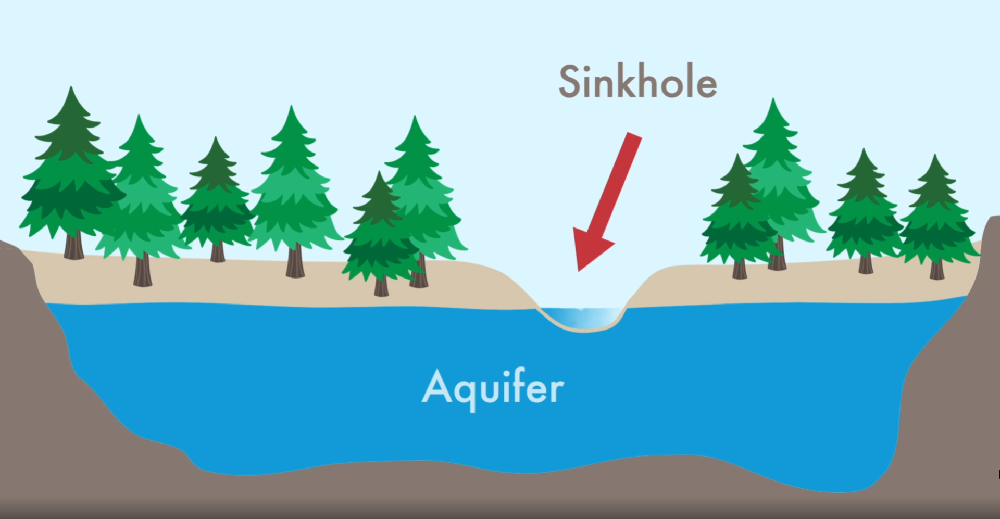

How do hidden water sources like this exist? Through groundwater, which seeps down into the aquifers, recharging them. Natural land, especially forest land, is critical to the existence of these important water sources.

Forest Land Serves as a Recharge Zone for Aquifers

More than half of all drinking water in the United States originates in forests, according to the National Association of State Foresters. And that’s not just from protected park lands. Close to 30 percent of drinking water comes from privately-owned, working forests, according to this article by the U.S. Forest Service.

“Forests are a recharge zone for groundwater. They’re not paved, they’re not covered with any kind of commercial activity. It’s open land with a lot of vegetation and trees,” says Rayonier’s Environmental Affairs Manager Janet Price, a biologist who guides the company on water quality and other environmental standards.

“That’s a valuable resource, particularly in parts of the country where an aquifer is the water supply for people who live in the area.”

Forest land allows water to sit and slowly seep into the ground, replenishing the aquifer. The roots of the trees and other vegetation hold soils in place, preventing washouts and erosion. As the water slowly percolates deeper into the ground, the root systems, soil and underlying permeable rock formations serve as a filter, naturally removing impurities from the water. In the same way, forests slow and filter water runoff as it makes its way into streams, lakes and reservoirs.

Green Infrastructure Becoming a Part of the Solution to Water Supply Needs

Forests and other green infrastructure, such as wetlands, have such a positive impact on water quality that communities around the world are incorporating green infrastructure into their water plans. One great success story in the U.S. is New York City. It uses the watersheds of the Catskill Mountains to provide what is known as one of the highest quality metropolitan drinking water supplies in the world. By investing in this green infrastructure, New York was able to bypass plans to build a multi-billion dollar water filtration plant, as explained in this article by the National Alliance of Forest Owners.

Best Management Practices Protect Water in Working Forests

Many years ago, in the early 1900s, our industry didn’t know how to properly protect waterways during forestry activities. But as the scientific community discovered what was needed to protect water quality and the ecosystems that depend on clean water, the way we work in our forests changed.

Today, sustainable forestry companies like Rayonier are guided by Best Management Practices (BMPs). These science-based standards specify how to protect various bodies of water in our forests. Each state has different guidelines for different sizes and types of water systems.

One of the most important aspects of BMPs are Buffer Zones, also known as Riparian Management Zones (RMZs) or Streamside Management Zones (SMZs). Spanning anywhere from dozens of feet to hundreds of feet, these areas are separated from the rest of the forest. Within these zones, the guidelines may call for little or no roads, heavy equipment and forestry activities. Harvesting within the area may be limited or eliminated altogether.

“We’re not touching the land very often, but when we do, we map out the buffers along the waterways that are off limits,” Price says, explaining that forests grow for decades with very little human interaction.

Foresters are trained to protect and monitor these areas during all forestry activities, as one of our foresters explains in this video about Cruising Timber. Rayonier foresters protect 11,800 miles of streams on our land, as of July 2020.

Taking a Proactive Role in Protecting Water in Our Forests

Recognizing the critical role our forests play in protecting water quality, Rayonier has worked with partners to not only protect, but to improve the quality of the water systems on our land.

Diverting Water to Brooks Sink, Florida’s Largest Sinkhole

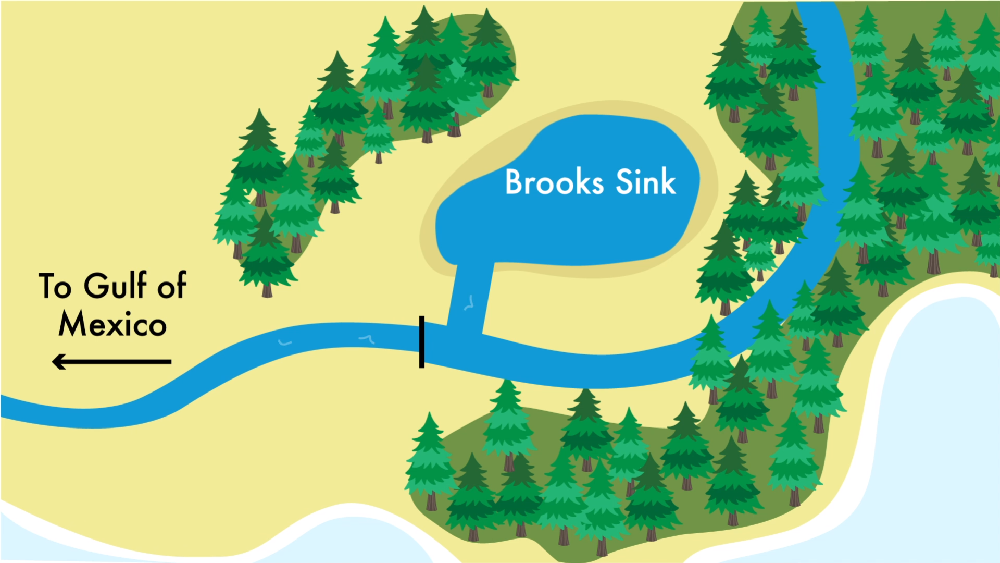

One of our Bradford County, Florida, forests contains a Florida wonder: the largest sinkhole in the state, as shown in the video above. Spanning about 200 feet across, Brooks Sink is a major source of water to replenish the Floridan aquifer. In 2000, Rayonier acquired the property where Brooks Sink is located. We soon found out there was an opportunity to make the sinkhole do much more to replenish the aquifer.

Back in the 1970s, it was a common practice on agricultural and timber properties to install ditches. They increased groundwater flow and made more of the land plantable. Foresters today recognize the importance of protecting natural drainage patterns and restoring them when the opportunity presents itself. Brooks Sink was one such opportunity.

About 50 years ago, water that had once flowed naturally into the sinkhole was diverted into a ditch which fed into increasingly larger streams and rivers. The water ultimately fed into the Gulf of Mexico instead of the aquifer, and millions of gallons of drinking water were lost.

We worked with the Suwannee River Management District to direct more of the water toward the sinkhole, the way it had naturally flowed before. The district installed flash board risers that slowed the water flow toward the Gulf, diverting a large proportion of it toward the sinkhole.

The riser sends an estimated 220 million more gallons of water per year into the sinkhole, enough to fill 333 Olympic sized pools to capacity each year, according to the Suwannee River Management District.

“It’s a very unique and special project,” Price says. “I don’t know of any other public-private partnership remotely close to that.”

Restoring Optimal Salmon Breeding and Rearing Conditions

In our Pacific Northwest forests, water protection has changed drastically for the better. Many of the roads and bridges in our forests were built in the early 1900s before our company even existed—and before the needs of the salmon population were understood.

When Washington’s salmon population began to sharply decline, the scientific community looked for answers. They found that the bridges and culverts below Washington’s road systems weren’t sufficient to maintain the natural flow of fresh water salmon need. Without being able to access the shallower upland waters, salmon didn’t have a safe place to breed and rear their young.

Washington passed the Forests & Fish law in 2000 to set a standard for water flow near roads and bridges. Since then, the forestry industry has been replacing whatever hinders the water flow, opening miles and miles of streams to salmon for the first time in a century. We work with marine biologists and other experts to ensure each project is good for the fish population both when and after work takes place.

Rayonier alone has invested more than $22 million in the program over the past 20 years. In that time, we’ve upgraded or removed 750 culverts and bridges, restoring 220 miles of stream habitat.

To learn more about the program, you can see our video and article, How Foresters Restore Salmon Habitat in the Pacific Northwest.

Of course, the project has benefited much more than the salmon population, restoring optimal conditions for entire ecosystems that depend on the clean, cool waters of the Washington uplands.

Taking Pride in Protecting America’s Water

Price says forestry has one of the lightest touches of any type of land use.

“We maintain the land in a way as close to natural as you can get it and still allow it to be productively utilized,” she says.

When we do work in the forest, we take special care to protect the land and water. Buffer Zones are protected from fertilization, which typically happens only twice in a forest’s decades-long lifecycle and was found in this recent University of Florida study to have a negligible impact on water quality. On our steep slopes, we use techniques like tower logging—which lifts logs high into the air with a skyline cable— to ensure we prevent sedimentation. And we replant our forests as quickly as we’re able to after they’re harvested.

Price says forests are one of the most important keys to current and future water quality nationwide.

“America’s water quality would not be where it is today if forestry had not progressed to what it is today,” she says.

Leave a Comment